You may have never heard of Stanley Whitaker. Not so in the world of progressive rock, where he and his outrageous talent on guitar has earned the admiration of thousands of prog rock fans, as well as the respect of prog icon Peter Gabriel, who wanted Stanley to be part of his back-up band. He’s that good.

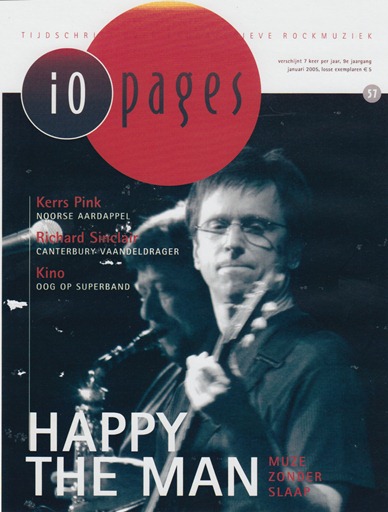

Stan’s band, Happy The Man, and their music still have fans around the world, though the band hasn’t been together for almost a decade. The highs and lows of Stan’s existence have given him an experientially wealthy perspective on life. His highs came from making the music he loved and the thunderous applause from appreciative audiences. The serious lows kicked in when Stan learned he had a rare form of cancer.

Triumph and Disaster. What makes Stanley’s story so affecting is how he faced them…

ATI: First things first. Tell me about your parents and your relationships with them, and, I’m just curious, was religion a big part of your family life?

STAN: No. Religion was not a big part of our family life. I have vivid remembrances of going to Sunday school and some of that, but we never went to church past that. I don’t know if it was because we moved around a lot—each tour of duty was a 1-1/2 to 2 years. The stint in Germany was three years but that doesn’t happen too often. It was usually a 2-year stint, and then you moved somewhere else.

STAN: No. Religion was not a big part of our family life. I have vivid remembrances of going to Sunday school and some of that, but we never went to church past that. I don’t know if it was because we moved around a lot—each tour of duty was a 1-1/2 to 2 years. The stint in Germany was three years but that doesn’t happen too often. It was usually a 2-year stint, and then you moved somewhere else.

ATI: Because you were an Army brat.

STAN: Yes. Both my parents were from Missouri. They were from farmer families, and my Dad joined the Army very young, went through all the ranks and ended up a full colonel in the Army. He served in three wars (WWII, Korea and Viet Nam) and had a very strict upbringing. Pretty typical for a lifer in the Army, as they called the veterans there, but it was good. They filled me with good, “Leave It to Beaver,” type morality, and that was probably my favorite show when I was a kid was, “Leave It to Beaver” and “The Andy Griffith Show,” too. I adored those shows. There was something charming about them—something just charming about that era–they instilled their own morality, and that’s pretty much what I grew up with.

ATI: Did you have difficulty making friends, or were you afraid to make friends because you knew you would be gone?

STAN: It was hard to make friends, because you knew you’d make them, and then you’d move somewhere else; partly because of that, I developed a really bad stutter. Whenever I would be in a brand-new school, and they’d have me stand up in front of the class, I’d get stuck on my middle initial, which is E, and I have vivid memories of “Stanley E. E. E.” I would get caught on the E. I put it to the fact that I was somewhere different. I was very uncomfortable—I had to make new friends every 1-1/2 to 2 years, and I was very shy.

ATI: How long did the stutter stay with you? Did you have to take any kind of speech therapy or anything?

STAN: It lasted until I moved to Germany and, around 11th grade, it pretty much had stopped. Basically, my brain was going faster than my mouth was able to keep up with, so I just learned to slow the thoughts down a little bit and think about what I was saying, and then I didn’t have as much trouble with it. Every once in a while I’ll still get stuck on something. But, it was a big deal all the way through 11th grade.

ATI: You were born on June 27th, 1954 in Monett, Missouri. Was there an Army base in Monett, Missouri?

STAN: There is an Army base real near there. Both my parents’ families were from that area—Monett and Joplin. Joplin’s the place that got hammered by all the hurricanes (2011). That’s where my father was from, so I was actually grateful that he wasn’t alive to see that devastation when it happened. That’s where they were from, and they would go back there to visit. They probably just went back there to visit family, because my remembrances are more Army bases throughout the state of Virginia and in Germany.

STAN: There is an Army base real near there. Both my parents’ families were from that area—Monett and Joplin. Joplin’s the place that got hammered by all the hurricanes (2011). That’s where my father was from, so I was actually grateful that he wasn’t alive to see that devastation when it happened. That’s where they were from, and they would go back there to visit. They probably just went back there to visit family, because my remembrances are more Army bases throughout the state of Virginia and in Germany.

ATI: How do you think your good fortune (at least, to us) to be able to experience life in other cultures like Spain and Germany affected you and the way you grew up?

STAN: A whole lot. Spain wasn’t as earth-shaking as Germany, but the two years in Spain, I was 8 and 9 years old. Spain was actually kind of scary to me; I remember there weren’t too many Americans over there at all, and the Spanish kids were not very nice to us, and I remember having rocks and dirt clods thrown at us.

The two years we lived in Spain were not really very pleasant, but my Dad was good about taking us around all the sights, and we’d go visit southern Spain and Valencia and Segovia. He was a real historian kind of a guy, so that was a really cool thing about him as a Pop. When we were kids we thought we were being dragged to a lot of these places, but now I have a much greater appreciation for all the places he took us, especially when we lived in Germany. That was from ’69 to ‘72. Living in Germany for three years was probably the most evolutionary time of my whole life. That particular tour of duty was absolutely life-changing

ATI: Did you learn how to speak Spanish and German?

STAN: A little bit of Spanish, but not a lot. It was required in the little American school we attended, and in Germany, it was the same thing. You had to take German, and I seemed to be much more adaptable to German than I was to Spanish, so I did speak German pretty fluently while I lived over there. It was a good time to be there, because the music there was so different than what was over here. To hear bands like Yes and King Crimson in 1969—it was very revolutionary for that time. And I probably wouldn’t have been exposed to that genre of Progressive music if I had not been over there or, at least, I would not have been exposed to it for 2-5 more years if I had stayed in the states. I just remember concerts being really cheap in Germany, and we would go see bands just because they had a cool name. That’s how we got exposed to Vander Graff Generator and Gentle Giant and a lot of those Progressive bands that aren’t as popular as Yes and Emerson, Lake and Palmer and King Crimson. I got to see the very first Emerson, Lake and Palmer concert ever, their very first performance. They showed up with Keith Emerson and walls and racks of synthesizers and stuff; it took them three hours to set up all his insane, early synthesizer stuff while the crowd is out there. They were three hours late, but they came up and said, “This is our first ever show.” I got to see a lot of monumental events over there—Pink Floyd with full choir and orchestra—stuff that just didn’t make it over here, unfortunately.

ATI: And, at the time, your relationship with your parents was good?

STAN: It was good, but it was also strained, because my Dad wasn’t around a lot. My Mom was, so she raised us much more so than he. We mostly saw him on the weekends or late at night. He was the one that brought my first guitar home when I was 8 years old, and he was the one a few years later that would say, “God, you are always playing that damn guitar. You know you can’t be a musician.” And my mother would say, “Well wait, you know the kid’s got a little bit of talent here. Let him play the guitar.” She always stood up for me and my brother on the music and art side of life. My father later resented bringing the guitar home, because it was “damn hippie musicians” and that whole scene. He didn’t quite realize what he had brought home and started.

ATI: You spoke about your brother Ken. What type of relationship did you have with him growing up?

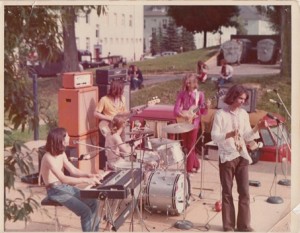

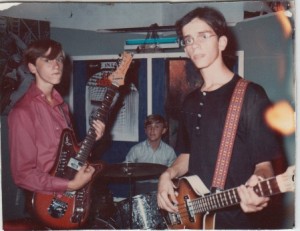

STAN: Ken and I were really close. He was two years older than I and, in a lot of ways, he was my mentor musically and artistically. He was quite an artist even though he didn’t get much support for that from my parents. He was a very unique, very original artist, and I really looked up to him. He was always on top of all the best new Prog bands. He just had to pull from what was hip and what was new coming out, especially while we lived in Europe. Yeah, we had a good relationship. He played the bass and sang a little bit. The final summer we lived in Germany, the summer of 72, I graduated. Ken had graduated two years before me, but we got to travel to all the Army bases. There were 48 of them throughout all of Germany, and he joined the band (Editor’s Note: Shady Grove—more on this later) because my Dad was actually [sent back to the US] and my parents felt a little better about me staying over there with my older brother there to watch over me. So we got to tour all these bases the whole summer, and that was a wonderful, magical time, too. He would stand on stage and sing and, while he was singing, he would paint pictures.

STAN: Ken and I were really close. He was two years older than I and, in a lot of ways, he was my mentor musically and artistically. He was quite an artist even though he didn’t get much support for that from my parents. He was a very unique, very original artist, and I really looked up to him. He was always on top of all the best new Prog bands. He just had to pull from what was hip and what was new coming out, especially while we lived in Europe. Yeah, we had a good relationship. He played the bass and sang a little bit. The final summer we lived in Germany, the summer of 72, I graduated. Ken had graduated two years before me, but we got to travel to all the Army bases. There were 48 of them throughout all of Germany, and he joined the band (Editor’s Note: Shady Grove—more on this later) because my Dad was actually [sent back to the US] and my parents felt a little better about me staying over there with my older brother there to watch over me. So we got to tour all these bases the whole summer, and that was a wonderful, magical time, too. He would stand on stage and sing and, while he was singing, he would paint pictures.

ATI: Why did he do that?

STAN: He was just a really strange, eclectic fellow; it was nothing we ever talked about. One night, he brought an easel onstage and, while he sang, he doodled on this thing. It was just him being an eclectic arty guy, and we let him do it.

ATI: Wow. Describe your introduction to music. When did you first even notice?

STAN: I had a great-aunt named Fannie Mae. Fannie Mae Henbest lived in Washington, D.C. and was married to a wonderful man named Lloyd. Lloyd was an archaeologist/geologist kind of guy. He was always interesting and had all kinds of wonderful stories and slide shows of his most recent visits to Africa or wherever. He was a curator at the Smithsonian during the fifties and would take the whole family around for private tours. He also worked for National Geographic. He was a really cool guy and his wife, Fannie Mae, was a wonderful classical pianist. I remember going to their little apartment in Georgetown; they had two huge turn-of-the-century, nine-foot Steinway grand pianos side by side in one room, and I would always wonder how they got those pianos in there. They told us they had them put in when the building was being built during the 30’s or 40’s, so the pianos were “flown” in through the side of the building. It didn’t make sense to me, but they were real interesting.

STAN: I had a great-aunt named Fannie Mae. Fannie Mae Henbest lived in Washington, D.C. and was married to a wonderful man named Lloyd. Lloyd was an archaeologist/geologist kind of guy. He was always interesting and had all kinds of wonderful stories and slide shows of his most recent visits to Africa or wherever. He was a curator at the Smithsonian during the fifties and would take the whole family around for private tours. He also worked for National Geographic. He was a really cool guy and his wife, Fannie Mae, was a wonderful classical pianist. I remember going to their little apartment in Georgetown; they had two huge turn-of-the-century, nine-foot Steinway grand pianos side by side in one room, and I would always wonder how they got those pianos in there. They told us they had them put in when the building was being built during the 30’s or 40’s, so the pianos were “flown” in through the side of the building. It didn’t make sense to me, but they were real interesting.

She was a brilliant pianist and would set me on her lap or next to her on her little stool and play classical music. That was my first true love of music and why, to this day, I just adore classical music. Especially Debussy. He’s my all-time-favorite composer in the whole world, and she was the first to play his music for me. For the first five years of my life, we would visit them a lot, because we were usually stationed somewhere in the state of Virginia. We would drive the few hours up to D.C. and visit them; it was always a delightful mix of music and archaeology.

They were wonderful. She even actually played for a couple of presidents when they would hold dinner parties, and she was John Kennedy’s pianist for his short reign, and 2 or 3 president’s before Kennedy. I don’t know if it was Truman or Roosevelt or another president, but she was his on-staff pianist.

ATI: You were also into puppets around this time. What was it about puppets that intrigued you?

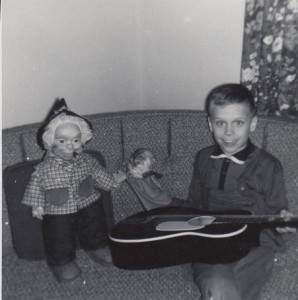

STAN: I don’t really know what first intrigued me with the puppets. I think as a little kid I remember seeing something I think was called Thunderbolt It was a really horribly done, almost sci-fi themed, rocket puppetry thing, but it was marionettes. I remember seeing that as a little kid and being fascinated with the string puppets, and it was like, wow, what the heck is that? And so we bought a few string puppets, and I just fell in love with them, and I had a few hand puppets. The marionettes were made by a British company called Pelham Puppets, and the hand puppets came from a German company called Steiff, which is famous for teddy bears. For me, it was a good escape. I didn’t really like talking; I knew I stuttered and was a shy kid, so using the puppets was another way for me to express myself. It has always been a fascination for me. Then, when my Dad brought the guitar home when I was 8 or 9 years old, I found a new love of those strings over the marionette strings. The puppets went to the wayside.

ATI: But you’re still into puppets. You and your wife, LeeAnne, are working on a project together.

STAN: LeeAnne and I have formed a company called Mother Nurture Fairy Tales, and our intent is to do some wonderful little 3-5-minute fairy tales with a wonderful, good old, “Leave It to Beaver”/Andy Griffith-kind of morality to it, but with some “Fractured Fairy Tales”-type of humor thrown in. One of my favorite cartoons as a kid was Rocky and Bullwinkle. Man, they were brilliant, because they really were written way above what we as kids were able to grasp; there was some very intelligent writing for that show—even musically. I think the music on that show is some of the coolest music ever from that whole period. Our intent is to do these wonderful little fairy tales with cool music, cool messages, do the whole production here at our house, put them out on You Tube and just have fun with it. Hopefully, it will be a viable product so we can make a living.

ATI: Let’s go back to your first guitar. You’ve said it made your Dad crazy later, so why do you think he brought it in the first place?

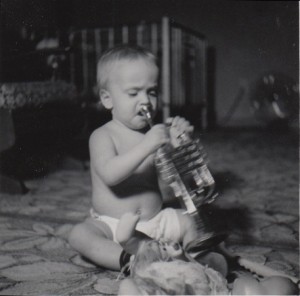

STAN: I don’t know. I think it was because we were in Spain and because the Spanish guitar is big over there. He was probably at the PX (the Army post exchange), and they had a cheap guitar there. For whatever whim, he just got it. It wasn’t something that I had expressed any interest in. For him to do something like that was monumental. He never brought stuff home, never unless it was a baseball or a football or something, so this was way out of character for him. It was a Stella acoustic guitar, and I remember the strings being a good half-inch off of the neck, ridiculously hard to play, but as soon as I picked it up, I just fell in love with it. I think it was a three-quarter-size guitar. It wasn’t a full size, but I’ve got pictures of me as a kid sitting on the couch with this little guitar and my puppets on either side of me. So it’s interesting—these are the loves of my life as a 4 and 5 year old.

STAN: I don’t know. I think it was because we were in Spain and because the Spanish guitar is big over there. He was probably at the PX (the Army post exchange), and they had a cheap guitar there. For whatever whim, he just got it. It wasn’t something that I had expressed any interest in. For him to do something like that was monumental. He never brought stuff home, never unless it was a baseball or a football or something, so this was way out of character for him. It was a Stella acoustic guitar, and I remember the strings being a good half-inch off of the neck, ridiculously hard to play, but as soon as I picked it up, I just fell in love with it. I think it was a three-quarter-size guitar. It wasn’t a full size, but I’ve got pictures of me as a kid sitting on the couch with this little guitar and my puppets on either side of me. So it’s interesting—these are the loves of my life as a 4 and 5 year old.

ATI: Nothing like first love!

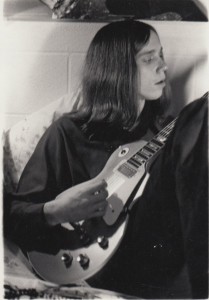

STAN: That got me introduced to and in love with the guitar, but I didn’t play it long before it was “Dad, Mom, this thing is really hard to play.” When we moved back to the states from Spain, I was 10 or 11 years old, and they bought me my first real guitar, which was a Goya Range Master; it was a really bizarre electric guitar that had all these weird split pick-ups and tons of buttons and knobs, but it was wonderful for me to learn on–much easier to play. I went through two years of guitar lessons with that guitar. A few years later, I bought a Gibson Les Paul, which was what I had been dreaming of and striving towards. The Goya went by the wayside, until an old friend said, “Man, I’ll buy it, because I don’t have a guitar.” I sold it to him and didn’t even think twice about it. The blessing is that he showed up some 40 years later at one of my shows down in northern Virginia, and said, “Hey, man, I brought your guitar back to give it to you.” I was floored. I now have back my original Goya Range Master.

ATI: Great story! So, were you a quick study at the guitar as a student?

STAN: Yeah, I was. I had a really good ear, or so I was told, and so I felt also. I went through this whole Mel Bay modern guitar method. It’s a 7-book course. It’s supposed to be a 3-5-year course, and I went through the whole series in two years. My teacher was quite astonished and realized that I was a cut above his normal student, and he told my parents that, too. So I had good support. They brought me to my lesson every week, and it was later that I think that my Dad really regretted it—“Oh, damn he is going to be a fucking rock musician.” He shouldn’t have brought that first guitar home,

STAN: Yeah, I was. I had a really good ear, or so I was told, and so I felt also. I went through this whole Mel Bay modern guitar method. It’s a 7-book course. It’s supposed to be a 3-5-year course, and I went through the whole series in two years. My teacher was quite astonished and realized that I was a cut above his normal student, and he told my parents that, too. So I had good support. They brought me to my lesson every week, and it was later that I think that my Dad really regretted it—“Oh, damn he is going to be a fucking rock musician.” He shouldn’t have brought that first guitar home,  because as soon as I heard Jimi Hendrix in 1967, I was, like, “Okay, this is definitely what I want to do!” He was the first guitar player to really turn my head around to where “Oh, man! Okay! Gee! This is what I want to do!”

because as soon as I heard Jimi Hendrix in 1967, I was, like, “Okay, this is definitely what I want to do!” He was the first guitar player to really turn my head around to where “Oh, man! Okay! Gee! This is what I want to do!”

ATI: How did you feel when you played the guitar?

STAN: For me it was meditation. I could just practice for hours on end–and I did. I would practice 3-4 hours every day, really regimented. Some of it was just practicing scales, but a lot of it was letting the guitar sort of play me, and that was that was how I learned it and loved it.

ATI: Tell me about The Impostors and the talent contest?

STAN: That was my and my brother’s first little rock band. I was 11 or just turning 12, and we did a song called, “Little Black Egg.” It was one of my favorite songs. I don’t even remember hearing it much on the radio, but that was one of the songs I distinctly remember playing. There was a local talent show in some school auditorium, and our band won the talent show. The announcer saw the little blurb about the band, told the crowd the guitar player is only 12 years old, and the place went crazy. I was up there just smiling and, “Holy crap!” I thought, “I can do this!” It was my first little rock band and my first taste of people clapping for me, and I loved what I was doing.

ATI: What did you win?

STAN: I think we won some little plaque in a frame. It was nothing major, that’s for sure; oh, and the adoration of our schoolmates.

ATI: Okay. We’re huge Beatles fans around here. Tell us about the influence the Beatles had on you.

ATI: Okay. We’re huge Beatles fans around here. Tell us about the influence the Beatles had on you.

STAN: I didn’t like the early stages of the Beatles as much as from Rubber Soul on. I remember, as a kid, I was always having arguments with little girls and other people who just gushed. “Oh, the Beatles! I Want To Hold Your Hand!” I hated that era of the Beatles for whatever reason. As soon as Rubber Soul came out, which I think was in ’65, I went right out and bought it. Actually, the first album I ever bought was the Byrds’ Fifth Dimension—the one which had “8 Miles High” on it. That’s the first record I remember actually going out and physically buying. I think Rubber Soul would have been the second record I was ever allowed to go out and buy. To me, that record had transcended all the previous Beatles stuff to where I don’t know if they had started smoking pot or what. I think it probably coincided with them waking up consciously, because, to me, that was such a monumental jump from the record before that to Rubber Soul. To me, the Beatles were the first Progressive rock band, and I’ve had lots of fun discussions with other Proggers about that. “The Beatles? What are you talking about?” Well, to me, Progressive rock is and means, literally, music that can Progress and evolve from record to record, and the Beatles did that. What other band can you look at from record to record that had such monumental growth and evolution? And George Martin [the Beatles’ record producer] was a huge part of that for them. From Rubber Soul on, I believed they were the greatest band on the planet and absolutely my biggest inspiration and influence in all of music.

ATI: We concur. What did you have in mind when you began developing your own guitar technique? It must have been pretty intense.

STAN: Besides Jimi Hendrix, probably the first really Prog guy that I loved was Robert Fripp in King Crimson and also Steve Howe from Yes. I made a real point of actually learning every little lick that Steve Howe played; he was probably who I was emulating most at that point—somewhere between him and Jimi, which is an interesting spectrum. I wanted to do stuff that was along the lines of what Yes was doing, and then I heard Gentle Giant. Gentle Giant was, and still is, my all-time favorite Prog rock group. I think they were the most talented and gifted Progressive rock band on the planet and, unfortunately, did not get near the notoriety as Yes and Genesis and others.

Genesis was the other band that I saw early on. I saw them on the Trespass tour (1970), with a very young Peter Gabriel, when he was doing all the costume changes and all the really elaborate stuff. That was all tied into that Germany—a period of three years where I was seeing all those bands live, and that was the music that I wanted to emulate—a hybrid of Yes, Gentle Giant, King Crimson, Genesis, Vander Graff Generator. Those were the bands that really spoke to me the most. Jethro Tull took Gentle Giant under their wing and did many, many years of tours with them as their opening band, because they really loved them, too, and were trying to get them much more exposure. Gentle Giant was the band that probably had the most influence on me, writing-wise. I wanted to write music like Gentle Giant wrote, because of the instrumental passages more so than the vocal passages. Somewhere in between was the classical music stuff, the impressionistic, Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky; to me, those composers were Progressive rock composers, and they go way before the Beatles as far as the first true Progressive composers. These guys were writing stuff that, if you did it with a rock band, would absolutely be called Progressive rock. I always have an interesting discussion with the Proggers about that one, too. The dichotomy for me was, in the same breath, loving all this heavy Prog stuff. I’d also go to see bands like Free and Humble Pie when I lived in Germany, and I adored Paul Rogers [Free, Bad Company]. I thought he and Steve Marriott from Humble Pie were two of the best rock ‘n’ roll singers on the freaking planet. And early Deep Purple! I got to see them with Ian Gillan. During that whole era, I loved edgy rock stuff, too, so I would clash with some of the Proggers about that as well.

“How can you like Free and Humble Pie!?” And I was, like, “What? Are you kidding? This is great ball-busting rock and roll! How can you not like this?”

“Well it’s not Prog.”

“So fucking what if it’s not Prog? It’s good music. It moves me, and that’s it. So end of discussion.”

ATI: Like most of us. back then, you got into the hippie culture. Where did you smoke your first joint?

STAN: That would have been Germany. We moved there the summer of ’69, which would have been the start of my 10th year of high school. We lived in a little town called Oberursel, Germany, on an Army base called Camp King, which was about 20 miles outside of Frankfort. My dad was the Commander of that post. I think he was a Lieutenant Colonel then, or maybe he was a full Colonel by then. We had been there only one or two days, and on my second day there, I was walking around the post, and a couple of GI’s said, “Hey, man, you want to hear some Led Zeppelin?” I was, like, “Led Zeppelin? What is that? I never heard them.” GI: “This album just came out, man. We just got it. Why don’t you come in and check it out?” First they pulled out the record (the first Led Zepplin album!), put the record on, and then found out I was the post Commander’s kid, and they were, like, “Oh really? Okay. You want to get high?”, and I was, like, “Yeah, what is that?” So, in the background, there’s the first Led Zeppelin album playing, and they break out a bowl of hash. I had never smoked pot or had anything at all to do with drugs. This was my first encounter with hashish, and, yeah, it was a monumental earth-changing evening to get stoned for the first time with these guys, who were getting a kick out of it because I was the post Commander’s kid, and they were turning me onto drugs and Led Zeppelin all in one fell swoop. That was my wake up call to Germany, drugs and some good, hard-rock music.

ATI: Well, let’s talk a while about Germany and high school. How did that experience influence your life?

STAN: I would say having the opportunity to go to high school over there was a gift, a wonderful gift, because I was living in and learning a different culture. I had the good fortune to hear and know the people, see the museums and see all the really cool architecture. I loved doing that, but on top of that, I attended Frankfurt American High School; they had a handful of serious college professors who had been at universities in the states and were fed up with the Vietnam War. These guys were basically radical college profs who got tired of the states and said “Fuck it. We’re moving to Germany to teach over there.” A teacher named Mr. Minette was my biggest mentor in high school.

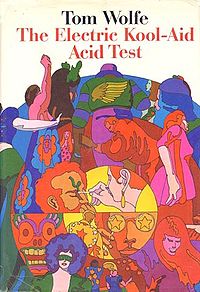

From 10th grade on, these guys were turning me onto the coolest books to read. I remember, on the first day of class, Mr. Minette handed out The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test by Tom Wolfe—the first book I read in 10th grade in 1969. I never heard of these guys. It looked like fun. Over the next three years, we read everything by Kierkegaard, Camus—every existential writer. These guys were just out there, and they were subversive, and I loved them. To me, they were brilliant. You’ll love this. I think I was in 11th grade for this test given by Mr. Minette. Final test of the year, and the essay question is “Who is the greatest rock band in the world?” It had absolutely nothing to do with our year of English and reading study, but that was the final essay question. Mr. Minette was a huge Rolling Stones fan, so if you didn’t answer the Rolling Stones, you basically flunked the test. I and another friend, Tony Brown, were in Minette’s advanced class, and we always had wonderful back-and-forth with this guy. He loved it because we were both smart and would have some intelligent discussions with him. We answered with the Beatles. I went into a three-or-four-page dissertation as to why the Beatles just absolutely blew the Rolling Stones off of the face of the earth when it came to being the greatest rock band. It was a brilliant little essay, and he gave me and my friend Tony both an A+ on the test.

From 10th grade on, these guys were turning me onto the coolest books to read. I remember, on the first day of class, Mr. Minette handed out The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test by Tom Wolfe—the first book I read in 10th grade in 1969. I never heard of these guys. It looked like fun. Over the next three years, we read everything by Kierkegaard, Camus—every existential writer. These guys were just out there, and they were subversive, and I loved them. To me, they were brilliant. You’ll love this. I think I was in 11th grade for this test given by Mr. Minette. Final test of the year, and the essay question is “Who is the greatest rock band in the world?” It had absolutely nothing to do with our year of English and reading study, but that was the final essay question. Mr. Minette was a huge Rolling Stones fan, so if you didn’t answer the Rolling Stones, you basically flunked the test. I and another friend, Tony Brown, were in Minette’s advanced class, and we always had wonderful back-and-forth with this guy. He loved it because we were both smart and would have some intelligent discussions with him. We answered with the Beatles. I went into a three-or-four-page dissertation as to why the Beatles just absolutely blew the Rolling Stones off of the face of the earth when it came to being the greatest rock band. It was a brilliant little essay, and he gave me and my friend Tony both an A+ on the test.

There was a really cool mutual respect, and these were heavyweight college professors who weren’t used to teaching kids that didn’t have the ability to have their roots shaken. Mr. Minette liked to shake people by their roots; and he was a bit abrasive and a bit abusive. I remember kids getting destroyed by him and crying and leaving the room in tears. “What are you, an idiot?” He didn’t pull punches, yet there was something that I admired about him even though he was a bit abusive. They were my mentors, and they woke me up to all types of religion and philosophy and stuff that I never would have got at any other high school in the US. That’s for sure.

ATI: So what is your philosophy of life now that you’ve had a chance to live?

STAN: It’s a mish-mash of a lot of stuff but I’m universal. I believe in a force called God, and I believe that there’s a flow in the Universe, and that you interact with that flow however you choose to. I believe that life is a gift, be nice and be good, and there are lot of Jesus’ teachings that I take into account. I think we are all children of God. We all have to and should be in touch with that part, and that part is innately within all of us. I believe it’s a place of purity and of good, and I try to live in that place as much as I can. If there are forces and people around me that are not of that same ilk, I simply remove myself or those people from the equation. Life is short, especially at this stage of my life, so I live with a good heart and with good intent and hope to be treated the same way.

ATI: Sounds good to me. Okay. Switching gears. Ulysses was actually your second band after The Imposters. How long were you with Ulysses?

STAN: Ulysses was 10th grade in high school, and 11th grade was another band, Shady Grove. Ulysses was my first band in high school, and I still keep in touch with some of those same guys. Some of them are still around in the D.C. area. That was a real fun band, because we did some of our own songs. It was really my first experience with writing some of our own music, and we wrote pseudo-Progressive stuff. We played a lot of Jethro Tull, and it was a very artsy Proggy band.

ATI: Let’s talk about the music you wrote and any lyrics that you wrote. What inspired you?

STAN: Lyrics, unfortunately, were not my strong suit. My brother was great with lyrics so, at that point in time, there was usually other people tasked with writing lyrics. I was responsible for writing music. I was always really good and quick at writing music. That was a natural gift and, even to this day, writing lyrics is a bit of a chore for me. I do it ass-backwards. Actually, I do it the way I just discovered Paul Simon writes a lot of his songs, which floored me. I think he’s a wonderful song writer and lyricist, and he writes the same way I do, which is to write all the music first. I even write the melodies of what I think the vocals should sound like, and then I fit words to the melodies. It’s an ass-backwards way of writing lyrics. I don’t recommend it to most songwriters. If you have the ability, write your lyrics first and then put the music to the lyrics. Lyric-writing has never been my gift. My wife can write some really good lyrics. She and I are working on some of our own music. When I do write lyrics, I attempt to tap into something of the spiritual realm and beliefs that we chatted about earlier. I figure, if you’re going to say something with lyrics, you might as well say something that’s going to touch somebody and hopefully help them grow in some way.

ATI: Absolutely. So here we are at your first tour. What was it like? Was it everything you dreamed it would be?

STAN: Yes and no. We did a lot of college tours with Happy The Man, and those were a lot of fun. For whatever reason in that period of time, there were a lot of very receptive colleges and college audiences, so we got to do a lot of wonderful shows in that regard. Arista Records would line us up little short stints. We did an 8-10-day tour with Hot Tuna, which was not a good mix musically. I remember those guys actually coming backstage to us on a few of the shows and saying, “Well it’s pretty ratty out there guys. You might not want to go out tonight. You’ll still get paid, but how about you just not even go out?” That happened on at least two of those dates.

I remember at the Commack, Long Island Arena, in front of 10,000 people, we went out and got through maybe forty-five seconds of our first song before the whole crowd was chanting “Hot Fucking Tuna” at the top of their lungs and throwing beer bottles and shit up on the stage. And we’re saying, “Oh my God, okay, they don’t like Prog rock here.” That was one big farce of a tour. Some of them were in much smaller places and some of those were actually pretty good. We would get through three or four or five or six songs, but it wasn’t a fun thing. Then we got a little leg on the first Foreigner tour ever. It was a much better match-up musically, but I think we only did three or four dates with them, and that was pretty cool. We did a lot of one-off shows in a lot of theaters. We opened for Renaissance, Stomu Yamashta and The Go Band—anything that was a regional East Coast thing with Progressive rock-type of band. We lucked into a lot of cool shows that way. But those were all just one offs. We never did any bona fide, two-or-three-month tours. Never had that opportunity.

I remember at the Commack, Long Island Arena, in front of 10,000 people, we went out and got through maybe forty-five seconds of our first song before the whole crowd was chanting “Hot Fucking Tuna” at the top of their lungs and throwing beer bottles and shit up on the stage. And we’re saying, “Oh my God, okay, they don’t like Prog rock here.” That was one big farce of a tour. Some of them were in much smaller places and some of those were actually pretty good. We would get through three or four or five or six songs, but it wasn’t a fun thing. Then we got a little leg on the first Foreigner tour ever. It was a much better match-up musically, but I think we only did three or four dates with them, and that was pretty cool. We did a lot of one-off shows in a lot of theaters. We opened for Renaissance, Stomu Yamashta and The Go Band—anything that was a regional East Coast thing with Progressive rock-type of band. We lucked into a lot of cool shows that way. But those were all just one offs. We never did any bona fide, two-or-three-month tours. Never had that opportunity.

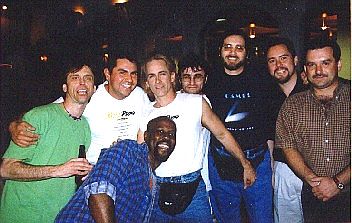

When Happy The Man was around, everybody, including us, knew that our audience was in Europe and not over here. It was 1978 or ’79, just before the band broke up, when we got signed, and our records came out. Disco was alive and well in the United States and just kicked our ass. We didn’t stand a chance over here. It was like, “man if we could only get to Europe,” but we didn’t have the means and didn’t know at all how to do that. I think, if Happy The Man would have been able to figure out how to get to Europe, it would have drastically altered our whole career. In later years, after we re-formed, Frank and I did a lot of interviews with a lot of European magazines, and all of them—across the board—were telling us, “Man, Happy The Man, you guys are in the same breath as King Crimson and Yes and Genesis. And we were, like “What? Are you kidding?” Being the humble, little Proggers that we are, it was hard to believe we had any kind of that fan base, but apparently, we do still have quite a fan base throughout Europe. We’ll never know. We never had the opportunity to play over there.

ATI: Let’s travel back a few years from there. Tell me more about your college life at James Madison, and how it led to the birth of Happy The Man.

STAN: I graduated high school in ’72, finished that fun Army base tour, and came back to go to Madison College in Harrisonburg, Virginia. A friend of mine from the band Shady Grove, David Bach, came back with me and was to be the keyboardist for Happy The Man. We didn’t even have the name yet, but while we were touring the Army bases, we met one of the Army guys at one of the first shows we did. A guy named Rick Kennell, who had just joined the Army, had a two-year stint to do before he got out. He was a bass player, met us backstage and played a Genesis song called, “The Knife.” We were, like, “Wow! This guy knows Prog, he plays, he’s very cool, and we hit it off so well that I said, “We’re going back to the states to go to school for a year or two, but when you get out of the Army, why don’t you look us up? You’d be a perfect bass player for this project we’re putting together.” That’s how we met Rick. We came back to the states to Madison College. David Bach didn’t work out keyboard-wise within the first couple of months. Then I met a guy named Frank Wyatt in one of my music  composition classes. He and I hit it off. He played sax, tenor sax and alto sax, and he had a jazz band I ended up joining. Frank was also a brilliant pianist and composer. He moved into my room, and we became roommates. We ended up rehearsing and making music in the dorm instead of being serious about school. While I was stilI in Germany, I had signed up for Madison as a music major only to find out when I got there that they don’t have a guitar major. They said I had to change my instrument, and I said, “Oh wonderful. You’re telling a music major that he has to change his instrument? Okay. I guess I’ll play violin because it’s got strings.” I made it my major even though it was a joke, because I couldn’t play violin for the life of me.

composition classes. He and I hit it off. He played sax, tenor sax and alto sax, and he had a jazz band I ended up joining. Frank was also a brilliant pianist and composer. He moved into my room, and we became roommates. We ended up rehearsing and making music in the dorm instead of being serious about school. While I was stilI in Germany, I had signed up for Madison as a music major only to find out when I got there that they don’t have a guitar major. They said I had to change my instrument, and I said, “Oh wonderful. You’re telling a music major that he has to change his instrument? Okay. I guess I’ll play violin because it’s got strings.” I made it my major even though it was a joke, because I couldn’t play violin for the life of me.

At least I got to stay there as a music major, and there was the jazz band. At least I could play the guitar with them. That’s how I met Frank, and we started Happy The Man. Rick was on leave from the army and went to get his drummer Mike Beck in Fort Wayne. The two of them came to Madison and stayed in our dorm room. We cleared all the furniture out of the dorm room and set up a whole band, rehearsed for the whole weekend and jammed. During that period we discovered this keyboard player from Harrisonburg, VA. His name was Kit Watkins, and both his parents taught piano at Madison College. To this day, I think he’s one of the greatest keyboardists on the planet. He’s a brilliant, gifted pianist—plays like nobody’s business. He had actually heard about Happy The Man, and he put up posters inviting anyone into Prog rock to come see his band—he had a little Prog group playing at the student union. He saw us come in, and he played Hoedown by Keith Emerson, played it flawlessly, and then he played some King Crimson. We were, like, “Oh, my God! Who is this guy?” Met him, fell in love with him and he became the keyboardist for Happy The Man. Kit was a real big part of the band’s sound, because we didn’t have any vocals, and the mini-Moog became the voice of the band. That’s how we all met, but we didn’t stay in school for the whole year. I think we both quit in the second semester, but still managed to live in the dorm for the rest of the year. We all took jobs around town, got a band house, where the band and the crew lived together.

ATI: Real jobs, you say? What did you do?

STAN: Oh, man. I worked in a hospital for a few years as an orderly—Rockingham Hospital in Harrisonburg. I was an orderly, and the nurses loved me. I was on the late night shift from 11 to 7 in the morning, and they would let me bring my guitar in and practice back in the orderly room. They were just wonderful. That was my main job. Before that, I was in construction, which I hated; cleaning up a Dunkin Donuts in the morning, which I hated. Frank worked at a paint store. All of us had crazy jobs, and there was a ton of work. There were a lot of factories around and a lot of chicken plants. I think Frank worked in a chicken plant. We worked at a place called Maphis Chapman, and we sucked soot all day in this factory setting for a few weeks. The orderly gig was the only thing that stuck with me—and that I stuck with. “Okay, this I can do. It’s a cool gig. I am helping people and the nurses love me. They let me bring my guitar to work, so I can practice.” I did that for 3 or 4 years.

ATI: When you were picking a different instrument at James Madison, why did you pick the violin over the piano? Wouldn’t somebody who was into Prog rock have opted for the piano?

STAN: Probably because I knew we had Frank, and we were looking for a lead-type keyboardist. I knew how to play a bunch of Beatle songs that I learned by myself, but I didn’t feel capable enough to make it a major. Part of me had always wanted to play the violin, so I thought it would be a wonderful challenge. I found a new respect for all violinists after trying to learn how to play it. It is a very tough instrument, but I still had fun learning it. I figured, if I had to go with another instrument, I would at least remain the string family.

ATI: We hear theatrics made your performances more than just a concert. How so?

STAN: Frank had a wonderfully brilliant mind for staging and coming up with wacky stuff. We all would feed it. “Let’s have clowns jump out. Oh, yeah! Clowns! Clowns would be great!” It would fill in for our lack of vocals. We flirted with a couple of vocalists early on in Happy The Man, but they didn’t work out. We knew our musical side was much stronger, felt we should remain just music and treated it like an orchestra. It was image-evoking music so it made sense to have slide shows and movies going on, as well as theatrics with dancers coming out occasionally. We would push the envelope. We didn’t care. We were pretty fearless in our youth—that 18- to 21-year-old period—and did some very adventurous stuff. We did a dinner-theater production called, “Death’s Crown,” which was a 45-minute piece Frank had written. It was a full-blown stage production with sets and dancers all the way. Usually, when we played live, we would just have a light show behind us. We had a three-man light crew doing the light show, film, slides and everything else. We thought the images helped with the feeling we were trying to put across—sort of a full-sensory experience. We knew a lot of our audience was high.

STAN: Frank had a wonderfully brilliant mind for staging and coming up with wacky stuff. We all would feed it. “Let’s have clowns jump out. Oh, yeah! Clowns! Clowns would be great!” It would fill in for our lack of vocals. We flirted with a couple of vocalists early on in Happy The Man, but they didn’t work out. We knew our musical side was much stronger, felt we should remain just music and treated it like an orchestra. It was image-evoking music so it made sense to have slide shows and movies going on, as well as theatrics with dancers coming out occasionally. We would push the envelope. We didn’t care. We were pretty fearless in our youth—that 18- to 21-year-old period—and did some very adventurous stuff. We did a dinner-theater production called, “Death’s Crown,” which was a 45-minute piece Frank had written. It was a full-blown stage production with sets and dancers all the way. Usually, when we played live, we would just have a light show behind us. We had a three-man light crew doing the light show, film, slides and everything else. We thought the images helped with the feeling we were trying to put across—sort of a full-sensory experience. We knew a lot of our audience was high.

ATI: Let’s talk about that, because you mentioned pushing the envelope. How far beyond pot and hash did you go?

STAN: It was an experimental time, and we tried everything—everything there was. I had no interest in powders like cocaine and heroin. I flirted with cocaine a couple of times, but didn’t understand why people liked that drug. I was already so buzzy, I didn’t need to do the speed-up thing. Heroin was just a ridiculous down, so I never had any flirtations or love for that stuff. It was mostly just marijuana and hash at that point, and then a few flirtations with LSD, which was something Frank and I did explore quite freely in the early 70’s to maybe ‘75. We explored on that realm because of our spiritual upbringing and all the reading we were into. Reading The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test in 10th-grade English awakened me to that world, and we read a lot of Carlos Castaneda. That side of life always intrigued Frank and me. We were the experimenters out of the whole band. Frank and I delved into that for maybe 2 or 3 years. We learned all we needed to learn on that drug, and it has since fallen to the wayside, which is probably good. I can’t imagine getting anywhere near that drug now.

ATI: Describe some the venues where Happy The Man performed?

STAN: Our favorite venues were the Warner Theater, which is a wonderful theater in Washington D.C. We opened up for Renaissance there. We played at the Ritz in New York City—a wonderful place. In Atlanta we played at the Agora Ballroom. We played there many moons ago. I remember that being a wonderful room. We played a couple of rooms in New Haven, Connecticut. Toad’s Place was a big room. Our favorite venues were the 2000-seats-and-below theaters. If it were any bigger, we just didn’t feel the same connection and we felt a little out of our element. The only time we played in bigger rooms was with Hot Fucking Tuna, and it wasn’t a great experience.

ATI: What was your offstage life like at the time? Where was home? Who did you hang out with?

STAN: We mostly lived all over Northern Virginia for that whole duration, moving between Virginia and Baltimore. Then there was a period when we lived in upstate New York up in the Catskills, which was after Happy The Man broke up and the band Vision was first formed.

ATI: How were you introduced to Paul Reed Smith and where did that relationship take you?

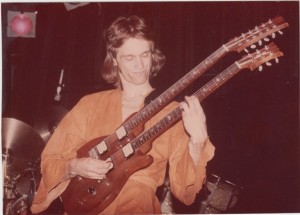

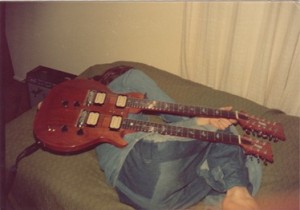

STAN: It was 1975. Rick and I were with Happy The Man, doing a concert somewhere in Annapolis. We were strolling down West Street when someone recognized us. They were coming to see us that night, and they asked if we’d heard of Paul Reed Smith. We’re, like, “No. Who’s that?” Turns out, he’s this young kid who builds guitars. “He’s up on the third floor of this little building here. You can just go right up to his shop.” So, Rick and I walked up to this guy’s shop. Here’s this little skinny kid, maybe 20 years old, carving on a guitar. We hit it off with him and couldn’t believe he was making these guitars by hand. He had only built a handful, maybe 3 or 4 guitars at that point, but he was one of these eclectic, gifted guys. It was kismet. We commissioned him to build a couple of guitars for us. He built Rick a bass, and he built me a double-neck guitar with a twelve- string on top and a six-string on the bottom. We were two of the first guys to commission guitars from him. He had built one guitar for Peter Frampton, and he had built one for a guy in a band called Artful Dodger, but those were some of the only ones he had built, and he gave those to the guys. We were the first guys to actually buy guitars from him, and he was ecstatic. We developed a wonderful relationship with him. He’s since become one of the greatest guitar builders on the planet and still builds a wonderful product to this day. I recently got both of my guitars back from him; I had them both refinished. They came out with a new color called” black gold” that I fell in love with, and I said, “Okay, you have got to do this to my guitars.” Paul’s a gifted guy who took the best of Fender

STAN: It was 1975. Rick and I were with Happy The Man, doing a concert somewhere in Annapolis. We were strolling down West Street when someone recognized us. They were coming to see us that night, and they asked if we’d heard of Paul Reed Smith. We’re, like, “No. Who’s that?” Turns out, he’s this young kid who builds guitars. “He’s up on the third floor of this little building here. You can just go right up to his shop.” So, Rick and I walked up to this guy’s shop. Here’s this little skinny kid, maybe 20 years old, carving on a guitar. We hit it off with him and couldn’t believe he was making these guitars by hand. He had only built a handful, maybe 3 or 4 guitars at that point, but he was one of these eclectic, gifted guys. It was kismet. We commissioned him to build a couple of guitars for us. He built Rick a bass, and he built me a double-neck guitar with a twelve- string on top and a six-string on the bottom. We were two of the first guys to commission guitars from him. He had built one guitar for Peter Frampton, and he had built one for a guy in a band called Artful Dodger, but those were some of the only ones he had built, and he gave those to the guys. We were the first guys to actually buy guitars from him, and he was ecstatic. We developed a wonderful relationship with him. He’s since become one of the greatest guitar builders on the planet and still builds a wonderful product to this day. I recently got both of my guitars back from him; I had them both refinished. They came out with a new color called” black gold” that I fell in love with, and I said, “Okay, you have got to do this to my guitars.” Paul’s a gifted guy who took the best of Fender  and Gibson and made his own out of it. He’s stayed true to his craft and his principals, and he’s a good guy.

and Gibson and made his own out of it. He’s stayed true to his craft and his principals, and he’s a good guy.

ATI: When did you move to D.C., and what happened there?

STAN: D.C. has always sort of been a home base, so I’ve always been around the northern Virginia area. Even now, we’re within an hour and a half from D.C. and northern Virginia. I’ve always had a lot of connections in this area from Happy The Man, and it seems a lot of the people from Germany ended up back in this neck of the woods. The whole East Coast region has been a good hub.

ATI: I’m going to go off on a tangent here. Why do you think Progressive rock is better received in Europe than it is in the U.S.?

STAN: I think European audiences have a better attention span. It’s more in their traditional bone to sit and listen and appreciate music, and then go nuts after the songs. In this country it seems that you go nuts during the whole song and after the song. The listeners over here don’t know how to sit and listen to what’s really going on. That’s the essence of the whole thing, and I noticed it especially after being in Europe all those years, seeing so many concerts and then coming back to the states to one of my first shows. Immediately, when the band comes out, the whole place stands up and stays standing up for the whole show. I’m, like, “What the hell is this? Sit down! Sit down and appreciate the music and, at the end of the song, stand up and go nuts.” That’s my analogy of one of the main differences, Maybe Europeans have deeper listening roots because of all the classical music roots that started in Europe. I think it’s in their DNA somewhat more. Music of a more sophisticated nature requires attention on the part of the listener. People in this country have a short attention span. A lot of Prog music has long, epic pieces, though Happy The Man did not necessarily ascribe to that. We broke with the Prog rock format by having some 3-4-minute-long pieces. But you still had to pay attention to appreciate what was going on in that 3-4 minutes. You’ve got to pay attention. You’ve got to focus on it.

ATI: Now we come to The Cellar Door. Why was it a great music venue, and what happened there to further the band’s career?

STAN: The Cellar Door was just a wonderful little venue. It maybe held a hundred people at the most. Right there on M Street, it was probably the coolest room in Washington D.C. The ownership really loved us, so we got to play there a lot. We almost became the house band there. I think there was a period when we were playing there every month. That’s where we  really got our roots in the D.C. area and became quite notorious. It was a prestigious room to play, and we played it so often, it helped get us well known in a short period of time. Real artsy, real dark, and they always had national acts. We were very fortunate to play there, because we weren’t a national act yet.

really got our roots in the D.C. area and became quite notorious. It was a prestigious room to play, and we played it so often, it helped get us well known in a short period of time. Real artsy, real dark, and they always had national acts. We were very fortunate to play there, because we weren’t a national act yet.

ATI: It was around that time you performed in front of iconic record mogul Clive Davis? What was going through your head when you played and what was his reaction?

STAN: I knew a lot about Clive Davis, so I was in awe of meeting him and playing for him, because he had just formed Arista Records. They brought us up to New York to do a showcase in a little rehearsal studio. It was very exciting. It was us up on a full stage with 7-10 chairs in the audience. Clive sat dead-center in the front row, relaxed back, closed his eyes, put his hands behind his head, his legs straight out, and that’s how he was for our whole 45-minute set. No real reaction or anything from him. A lot of the people around him were showing much more reaction and flipping out and clapping. He didn’t clap. He didn’t do anything. We had never done any showcases per se for any major record label, so this was our first experience. I think we did what we were supposed to do, because he came up afterwards, and the first words out of his mouth were, “Wow. I don’t really understand this music. It’s way above my head, but my head of A&R, Rick Chertoff says you guys are incredible, and we should sign you, So welcome to Arista.”

Thank God Rick Chertoff was there, because we wouldn’t have gotten signed if Rick hadn’t been there.

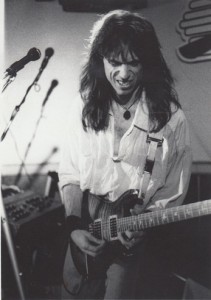

ATI: Why did you go to all instrumental just before you signed with Arista?

STAN: During the whole D.C. period, we had been an all-instrumental band, and that’s how we made our nut—doing full symphonic, instrumental shows with a cool light show. That’s what we were known for. That’s how Arista saw us. The showcase did not have a single vocal tune in it. So we got signed off on that, but when it came down to actually negotiating the contract, it became a sticking point. They said, “If we knew there was going to be hope down the road that there would be some vocals, we’ll sign you right this minute. But it’s a sticking point for us, because we don’t think an all-instrumental band has a shot in hell of making it.” Blah, blah, blah. Everybody in the band was looking at each other—“You want to sing? I don’t want to sing. Do you want to sing?” And I said, “Well, shit. I sang in choir. I’ll sing.” That’s how I started singing.

ATI: What was that like for you singing after all that time?

STAN: I didn’t care for it. I was the reluctant front man. I had always considered myself the anti-rock star. I had no interest in being a front man vocalist. I didn’t think I had that in my persona. I agreed because it was going to get us signed. They were going to sign us if someone sings a song, so we had to work up a couple of vocal tunes to be on that first album. That’s why there are only two and, on the second album, there’s only one. It was not our strength. Our strength was full-instrumental, symphonic music.

ATI: It was about that time Peter Gabriel showed an interest in Happy The Man. What happened?

STAN: Yes, it was at this same period. We had a really cool connection, because our bass player, Rick Kennell, had 2 or 3 dear friends who worked on the road crew for Genesis. Dale Newman and Dan Owen handled the guitars, and the main sound man for Genesis was a fellow named Craig Schurtz. He was Rick’s good buddy, and during the early period of Happy The Man, Rick had been passing cassette tapes to these buddies of his, and they had been playing them for the guys in Genesis. That was how they knew of us. In the spring of ‘76, Peter Gabriel had left Genesis, and he got into touch (or his management got in touch) with our management. Cellar Door loved us so much that their booking agency management firm took us over. They said they had five bands they were checking out to be Peter’s back-up band–two in England and three in the states—and we were one of the bands being considered. We were absolutely very interested, and we’d heard horror stories of all these other bands; Peter had walked in and spent 10 or 15 minutes, got frustrated and left. We were, like, “Oh, my God, he saved us for last probably because, having heard some of our music, he felt that we were going to be a little more of what he was looking for.” And we were the last band he checked out.

Peter was absolutely my favorite rock star hero in the world, because seeing him with Genesis—there was nothing like that. It was such a theatrical production that you left those shows altered, changed. They had affected me, and this guy was one of the biggest rock stars I had ever met. Peter came in, met us and sat down at the piano. He said, “Let me play you a little bit of what I’m working on,” and he closed his eyes, played a few chords, sang 1 or 2 lines, and then just stopped still with his eyes closed. I remember us in Happy The Man standing around kind of nudging each other. We’re thinking, “What? Are we supposed to say something? What’s he doing?” Then, out of nowhere, he just started singing again. It seemed the stuff was so new for him, that he was trying to think of where it would go next. It was the embryonic stage of the music, and we proceeded—over the next 7 1/2 hours—to work with him extensively on two of the songs. He used a lot of the arrangements we–especially Kit and me—came up with for two of the tunes on that first record.

Peter was absolutely my favorite rock star hero in the world, because seeing him with Genesis—there was nothing like that. It was such a theatrical production that you left those shows altered, changed. They had affected me, and this guy was one of the biggest rock stars I had ever met. Peter came in, met us and sat down at the piano. He said, “Let me play you a little bit of what I’m working on,” and he closed his eyes, played a few chords, sang 1 or 2 lines, and then just stopped still with his eyes closed. I remember us in Happy The Man standing around kind of nudging each other. We’re thinking, “What? Are we supposed to say something? What’s he doing?” Then, out of nowhere, he just started singing again. It seemed the stuff was so new for him, that he was trying to think of where it would go next. It was the embryonic stage of the music, and we proceeded—over the next 7 1/2 hours—to work with him extensively on two of the songs. He used a lot of the arrangements we–especially Kit and me—came up with for two of the tunes on that first record.

It was a wonderful experience. God, here we were playing music with Peter Gabriel—pretty powerful stuff—and he left very excited. He really liked the band. He told our management he wanted us exclusively. But, God, we had worked about six years to get a deal on the table from Arista Records. We really didn’t want to give that up, but we were willing to give his project top priority. I was staying at the manager’s house during this period of time, a fellow named Bob Steinem, and I can remember Peter calling almost every day to chat with me, to see if there was any way at all that he could get just Kit and me? We were the two of the band that he wanted. He would take the whole band, but he loved Kit and me. I said, “We’re flattered, but no. It’s the whole band or nothing, because this is family. We’d been together six years, and he understood that. We spent a good couple of weeks going back and forth, trying to figure out if we could do it, even with us giving his project top priority.

We ended up with no deal because he wanted us exclusively, and we weren’t willing to give up our record deal. But Peter’s wanting us so bad actually helped kick Arista in the ass to sign us quicker, so it was a blessing in that way. We did get signed to Arista, even though they dropped us two years later. In ’79, Peter’s management found out about Happy The Man breaking up and got in touch with me to see if I was interested in coming to England to work with Peter on or, at least, put some stuff on tape for Peter, because he was starting his third album and hadn’t gotten David Rhodes in the band yet. I was, again, extremely flattered.

If I have any regrets at all in my life (though I’ve tried to live life with no regrets), that’s the only one I can think of. I probably should have hopped on it, because it was a wonderful opportunity. Even my mother said, “Peter Gabriel. Isn’t that a fellow you like?” I said, “Yeah, he’s probably my favorite Progressive rock singer–period. And she said, “Well, don’t you think you should do that?” It was kind of cute hearing her think she knew about Prog.

At that point I had discovered this singer, a fellow named Rocky Ruckman, who I knew in my gut was a star. The guy just had a four-octave voice of full balls, like the most ballsy rock singer. Rocky was a cross between Steve Marriott and Ian Gillan, and he was a brilliant songwriter. He was interested in working with me, so that was the end of the Peter Gabriel story for me. I turned him down and went another route with my band Vision and Rocky.

ATI: Let’s talk about your time with Arista. How did you know to request Ken Scott the Producer at Arista?

ATI: Let’s talk about your time with Arista. How did you know to request Ken Scott the Producer at Arista?

STAN: Arista asked us who we were interested in producing our first album, and Ken was our top choice. He had just done Birds of Fire by the Mahavishnu Orchestra. We felt a kinship with the record and, with our style, we knew he was the guy we wanted. When they approached him, we learned he loved our music so much that he was willing to cut his normal production rate just to be part of it, because we didn’t have the budget to pay him his normal rate.

ATI: What was it like to work with him?

STAN: It was glorious working with Ken Scott. He was a living legend as a producer, having worked with the Beatles and Supertramp. He had done both Supertramp albums; Crime of the Century and Crisis? What Crisis? came out at that same time too. Ken’s list of credits was sick—Elton and David Bowie—he did all the early David Bowie stuff. He had stories like crazy. He was a story-teller, so we’d just sit and listen. It was part of his British personality. He would come into the studio every day with a scent of, what was it…not B.O. but some kind of scotch. He had an affinity for J&B scotch. He would come in every day with a fresh bottle and plop it down. By the end of the day, he would have gone through that whole bottle. I don’t know how he could drink that much; it was his poison of choice, but he was such a wonderful, gifted engineer/producer to work with—it was like going to school. We learned so much making those two records and heard so many wonderful stories about the Beatles, Elton, Ziggy and Jimi. He had great “war” stories, as we liked to call them. He developed such a love for us that, after some of the sessions, we would go back to his house and spend time with him and his wife in their backyard in the pool and Jacuzzi. It was a very friendly and warm relationship. It was a great gift working with Ken Scott.

ATI: Speaking of gifts, were you meeting any of your personal rock idols along on your journey? Do you have any stories?

STAN: One story in particular affected me when I was fifteen and a budding guitarist. Steve Howe (Yes, Asia) was my favorite guitar player on the planet. I knew every lick he did. It was one of my first times seeing him. Security was nothing in Europe. It was so easy to get backstage at shows over there, it wasn’t even funny, so we went back and talked to the guys in Yes. I remember Jon Anderson being sweet as can be and taking us up on stage, showing us the Mellotrons and all the gear. He was really spending quality time with us and it’s, like, “Wow! Here’s a really wonderful, gentle, pure spirit, just like his voice. This is cool. I want to be like this guy.”

Then Steve Howe emerges from the downstairs dressing room, and Jon said, “Steve, come here. You’ve got to meet this kid, man. You’re his hero. You’re his favorite guitar player. He knows every lick you play.”

Then Steve Howe emerges from the downstairs dressing room, and Jon said, “Steve, come here. You’ve got to meet this kid, man. You’re his hero. You’re his favorite guitar player. He knows every lick you play.”

I’ll never forget it. He looked at me, eyeballing me from head to toe. Granted, he had his coat on, he had his guitar, and he was ready to go. He literally looked me up and down, said, “Later, mate,” and walked away. It affected me so greatly that, from that day forward, I never heard Yes quite the same way. Wow, really? There’s a guy in your band who couldn’t be sweeter, who’s spending intimate time with us, and you can’t come over and say hello? You can’t even shake my fucking hand? It affected me so greatly that, on that day, I decided I’ll never be like this guy. It’s such a shame because he’s such a great guitarist, and the thing is, I’ve heard similar tales about him from other respected guitar players more recently who said, “Wow. That happened when I met him.” To me, if you’re in a profile position like he is and you don’t have the time to say hello to one of your fans, I think that’s fucked up. There’s something wrong with that. You owe that to your fans. I didn’t buy anymore Yes albums after that. The last album I bought was Close To the Edge.

ATI: They say should never meet your idol because, more often than not, you’ll be disappointed.

STAN: It was very true in this case. I want to put it out there to any and all aspiring musicians—man, retain your humbleness. Remember who you are because it’s going to come back and haunt you, if you don’t. I believe in being kind and nice. It’s pretty simple for some people, but difficult for others, I guess. I think it’s real smart to stay humble. Simple as that.

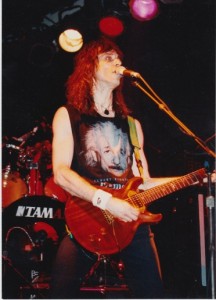

ATI: Now I’d like to hear more about Rocky Ruckman and Vision.

STAN: Rocky was in a band called Skywalker that opened up for Happy The Man in Cumberland, Maryland at a college. I heard this guy belt this stuff out, met him and said, “Man, if Happy The Man ever breaks up, I’m calling you,” and he said, “Man, I’d be honored.” Here was a guy with a gruff exterior and an 8th grade education who could sit down and write lyrics to a song in an instant. He just channeled it. He never crossed anything out. He would hear a piece of music—I’d play a little lick—and he would write lyrics. “Okay, finished!”—and they were brilliant. His lyrics were wonderful. He was a gifted fellow with an amazing voice.

We did a project with Eddie Kramer, the producer who did all the early Led Zeppelin and Hendrix albums, so he’s another hero of mine that I got to meet and work with. We did a brilliant eight-song demo with Rocky, and we actually got record companies interested; we performed in a showcase at the Ritz in New York for around 12 record companies. They came ready to sign that night, but Rocky went out and tried to be a sexy front guy, which was not his style. He was a gruff, rough-and-tumble, AC/DC-type of front guy. I don’t know why he did it, other than I think he was so uptight and nervous about all these record companies, and he had heard comments like, “He’s not a great looking guy,” and “Boy, he can sure sing, but, yeah, he is not real great to look at.” So he tried to be a sexier, Rod Stewart-like performer, alienating and turning off every single record company, so that was that.

We continued a little bit longer and actually had fun with it, but it became more of a half cover band and half original band after that. Until then, it had been all our own music but after that we decided to start doing covers, too, so we could play out and earn a living. Vision gave us a very successful livelihood around the Baltimore and DC region for 5 or 6 years. We opened up for a lot of major bands, but the band had run its gamut at that point. So David Bach and I did an offshoot of that band called One by One, which did mostly original music.

ATI: What was your life like when you were part of One by One? Were you fulfilled and happy?

STAN: Yeah, I really was. We were doing almost all original music, and it was a real fun period because 80’s music was in full swing. We had a really good rhythm section and could pull off a lot of the hipper 80’s music, as well as doing our own stuff. We were very successful in the northern Virginia/Baltimore region, but only that region.

ATI: So is that why you took Paul Reed Smith’s offer to take his place in the Band of 1000 Names?

STAN: Yeah. I knew about the Band of 1000 Names, which was the band Paul had played in for years. He was getting so busy with the growth of his factory he just didn’t have time to do it. The band had really great bass player named Carey Ziegler, who called me and said, “Man, I wonder if you’re interested in doing this thing with us.” I thought it would probably be fun; they were an all- cover band, but it was more rock—Eagles, Rush, Bad Company and other classic rock stuff. I joined and had a lot of fun for a couple of years. There were only 1 or 2 opportunities when Paul sat in, and we were able to play together. Paul is actually quite a tasty guitar player.

ATI: How did that lead to Avalon?

STAN: That would have been the very next thing. One of the keyboardists, a good friend of ours named Bill Plummer, is a gifted sound man (he did sound for Happy The Man during a lot of its hey-day). He did sound on one of the first Whitney Houston tours and for Anita Baker; he’d done a lot of major tours as the front house PA guy. He was also a very good keyboard player, especially on mini-Moog, because he took lessons from Kit Watkins back in the early- to mid-70’s. He had a lot of Kit’s mojo in his playing. Bill and I had toyed around with putting a cover band together that did nothing but hip cover stuff and did none of the standardized covers. We formed Avalon around 1990. We did Pink Floyd, Peter Gabriel, Jeff Beck and some King Crimson, basically picking our coolest, favorite proggy stuff over the years, and the band became very successful. We did it to fight against all the standardized rock played in all the clubs, and we honestly didn’t think it would be that successful. We were just doing it for ourselves, and a lot of times that seems like the best thing to do. If you do something for yourself and think it has value, hopefully it will have value for somebody listening. This band really took off. People just adored it; it was a lot of fun, and we made good money with it.

ATI: Eventually, you moved to L.A. Why?

STAN: I didn’t want to get to the end of my life and wonder, “What if I had moved out to L.A. and given it a shot?” So, the week of my 40th birthday in 1994, I moved out to Los Angeles.

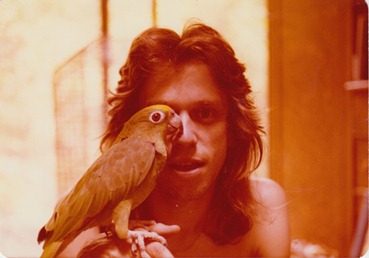

ATI: With Merlin the Parrot, I’m told. Tell us about Merlin.

ATI: With Merlin the Parrot, I’m told. Tell us about Merlin.

STAN: I had always been into birds, and he was the only pet I had at that point. Merlin was a yellow-headed Amazon parrot—a sweetheart of a bird. I rented a big Penske truck; I had a perch with a suction cup on it, and I stuck it on the passenger side window. He sat on his perch, and we drove across country. We got a third of the way across, got to a motel, and I put him in a tiny travel cage to sneak him in my room with me. We’d wake up the next morning and drive some more.

ATI: Did Merlin talk?

STAN: Oh, yeah, he talked a bunch. He had quite a vocabulary, mostly standard stuff. “Hi, how are you?” “What are you doing?” “Where are you going?” He had a couple of great laughs, and he had some loud squawks too. I had to get rid of him later because, in his old age, he got way nasty and very aggressive with anybody and everybody. People told me it was because he never had a girlfriend, and he was just frustrated. Whatever it was, he was biting the flesh of too many people.

I found a wonderful home for him with a lady who just adored him and he adored her. I knew he had a good home.

ATI: Where did you live?

STAN: North Hollywood. I lived with a dear friend of mine named Fred Brown. I went to high school with him in Germany. His older brother Tony and I were musical buddies. Tony played drums in Ulysses. Fred was Tony’s younger brother and a wonderful, wonderful friend–probably more of a friend than Tony at that stage in my life. We hung out all the time, and Fred invited me to live with him. Fred was a heavyweight lawyer for Warner Brothers Records for many years, and staying with him ended up being quite the gift.

ATI: Why’s that?

STAN: It’s a tough nut to crack out there. My buddy Fred made it much easier for me than someone moving out there fresh and cold. He knew the music scene and everything in that area, so I had the best tour guide I could possibly have. I wanted to go the singer/songwriter route; I had never done any solo acoustic and singing. They had a lot of rooms out there for it, and Fred told me about all the hip rooms. One in particular called Ghengis Cohen which was probably the most notable singer/songwriter room. I’d write music and go there to play it. I’d do my 15-to-20-minute set, which was as much as they’d let you play, and then they would shuffle in the next guy.

L.A. was the way I thought it was going to be; I presumed it to be an image-oriented place and that’s what it was. Everybody was either a musician or an actor or a model, but they were all working in restaurants, trying to make a go of it out there. It’s very much touch-and-go. I had to get other work, and there were a lot of temp agencies out there. That work was really cool, because I didn’t know where you would be from day to day. When I got a call, sometimes I’d be at Hanna Barbera, sometimes at Disney. Those were cool gigs for me because I was around cartoons I loved, seeing original cells from Bambi and some of the old classics. Then I got with one temp job with The Entertainment Coalition; it was insurance underwriting for the film industry. They offered me a full time position, and I became the manager of the file room there. That was my gig for most of my period out there.

ATI: Did you like working solo?